Just an indulgent reflection on my creative writing, Homestuck, Revolving Door, and the catharsis of multiverse fiction.

So picture 2014, mid-Megapause. That was the year Flight MH370 vanished, the year the ebola epidemic began. I was a year into my bachelor’s degree, and my father was battling Stage 4 cancer. That was the year I read Homestuck.

Up till then, my favourite works of fiction had been ones where personal narratives were rendered small and yet immensely important against a backdrop of geopolitics, tales where the protagonists were doomed from the start, or where the only victory possible was a Pyrrhic one. Think Lord of the Rings, Les Misérables (the musical), Oban Star Racers.

Importantly, these were all stories quite entrenched in the conventions of their genres—full of gravitas and sorrow, and perfectly sincere in their treatment of tragedy.

At some point, though, I realised I craved something different.

It was, of all things, Marvel’s Avengers that gave me my first toddling glimpse of what that might be. It presented to teen-me, and to the 2012 milieu, a highly visible and much-discussed work of fiction that united five fully-realised stories.

It wasn’t just that it united five stories, though. It was that it united five worlds, each with their own internal narrative logics—endemic worldviews, moral quandaries, character arcs, themes, and motifs. It reconciled them in a single work, in a way that felt like it developed each tributary work’s themes and characters consistently, both within each separate world and within this merged one.

I don’t view The Avengers with such a rose-tinted view now (seeing as the MCU went on to bring the concept of “franchise fatigue” into existence). But nevertheless, this was the work that seeded my interest in multiverse fiction, by using it not as a plot device, but as a rhetorical one. A trick of form, like a metaphor in a poem, or a repeating refrain in prose, to underscore its thematic weight.

Marvel had, in effect, simulated a crossover—on a scale and with a coherence I’d never seen prior to then.

I’m not sure how many people following me in the present know about my history of novel writing. Novels have always been my preferred way of realising narratives. It started with 100- to 200-page stories that I would write in between classes, while waiting to be picked up from school, at 2am under the light of my phone, and then on said phone.

From the ages of 14 to 18, these interests culminated in Of the Dragon, of the Stars, a stock-standard epic fantasy novel that began as MapleStory fanfic, took me 6 years to complete, and became my first taste of internet visibility. OTDOTS took me so long to write that I wrote another novel, Eagles and Swans, from start to finish, in the middle of its protracted run (it’s also a slightly better novel in my opinion; I’ve rewritten it 4 times).

Anyway, at the time when I watched The Avengers, I was tantalisingly close to completing OTDOTS, and already had in my mind the idea of starting something new and different. When I experienced Marvel’s simulated crossover, it suddenly clicked that I knew what I wanted that to be.

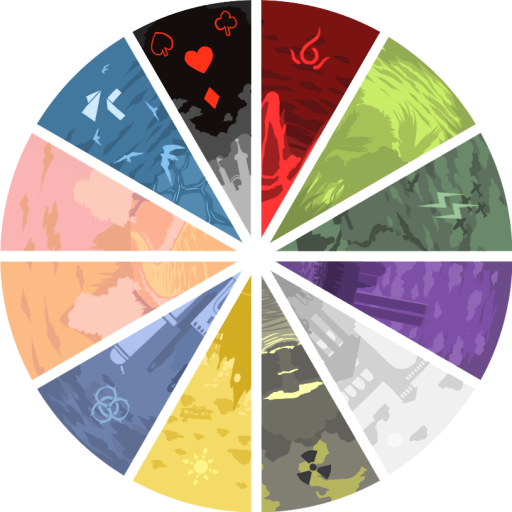

Revolving Door is what came of that. It was “the most complex story I could come up with” in 2012: a multiverse of 12 worlds (12 because it had been a long-time arc number for me), each one embodying a different fiction genre, each to be fleshed out as an independent story before its plot thread was pulled into the loom of the converging mega-plot.

It was taking the template of The Avengers and making it my own—simulating a crossover among the range of fiction genres I enjoyed, and trying to mesh their different narrative logics with each other. It had:

- A Wars of the Roses-inspired clockwork fantasy world featuring an expansionist empire with infighting noble houses,

- An islandic low fantasy setting drawing from Southeast Asian traditions with magic cast with folded cloth,

- A cyberpunk dystopia where four megacorporations have subsumed the US,

- A world embroiled in World War 2 well after it was meant to end,

- A Victorian solarpunk world centred on social and romantic drama against the backdrop of a solar technological revolution,

- A magic realism tale set on a fictitious Pacific island,

- A slice-of-life tale set in Boston,

- An alternate history where the Roman Empire never collapsed, and

- A nuclear apocalypse hellscape.

And importantly, it had one singularly important character—a child named Orobelle—who held all the universes together simply by being alive. Who, if killed, would bring every reality tumbling down.

RD would be designed to be readable in a flexible/nonlinear order (you could pick which universe to start with), but all of those plotlines would eventually converge into one. To that end, I made a story map…in 2024, after planning to for years.

Anyway, in the two years before I started writing RD, and for two more years thereafter, I’d been growing peripherally aware of a work of fiction called Homestuck. Two of my friends followed it, and when I described my incipient RD outline to one of them, the first thing they said was: Orobelle reminded them of a character in Homestuck whose heart contained the universe.

That didn’t immediately mark it in my mind as a work of fiction I wanted to read, but it did tell me a lot about Homestuck’s tone, scale and thematic threads: that it’s a story that engages with the scale of the universe, and employs the body as a metonym for reality. Just as I was doing in RD.

Well, I later noticed a pattern with Homestuck fanart: that each character seemed to be associated with firmly reiterated iconography like ghosts, atoms, and vinyl records…just like I did with my own writing.

And at that point, I caved and started reading it.

I don’t actually think Homestuck is unique in many of the ways that people believe it is. Messing with the interface to convey plot or themes is a beloved video game trope. Arc numbers have been done since time immemorial. Even fiction that speaks to and about its medium was done in the Thousand and One Nights. And nested universes? The Avatamsaka Sutra did it first.

But what Homestuck does with those influences, which any work with a metafictional bent tends to need to do, is draw from the fiction traditions that came before and re-present them for the cultural niche to which it speaks. None of these traits in isolation is unique, but Homestuck takes them and makes something new of them.

I read all that existed of Homestuck up to the Megapause in 9 days. I remember because I was keeping track. I would wake in the morning, start reading it, and not stop for anything except meals and bedtime. It gripped me and it never let go.

Then, in the ensuing months, I found that it had changed the way I wrote, for good. My writing always leaned heavily towards, let’s call it, the Tolkienian camp—meticulously attending to the internal consistency of its worldbuilding, asserting the total self-complete reality of its fictional universe, and rarely ever making fun of itself.

Homestuck is the weird great grandchild of Tolkien, via Dungeons and Dragons, then RPG video games. And along the way, it came to embody what feels like the opposite of Tolkienian gravitas. It pokes fun at the conventions that most stories are beholden to, and those that the audience holds in their minds as they read. It calls attention to its fictionality while at the same time keeping suspension of disbelief intact through immersive worldbuilding and character drama that relies on its metafictional commentary.

As in, Homestuck is about four kids trying to escape the game they’re in—a game that is responsible for their existence in the first place. Their reality—the reason they exist—is the webcomic, and their actions end up altering the interface and structure of the webpage itself.

And definitively—maybe most definitively—it uses the language of the internet.

We’ve had fiction that comments on itself for ages. And even among internet media, Animator vs Animation was a childhood staple of mine, so the idea of characters breaking the fourth wall by messing with the interface was never an alien concept. What is truly unprecedented about Homestuck is that:

- it is a commentary about fiction made for the internet,

- it is a cosmogony, a story about how a universe came to be, which lends it a religious heft that few other self-referential works attain, and

- it has something to say with those interface gimmicks—a thesis about the determinism of the narrative/reality.

And importantly, it does so without…being self-important? It never posited to be a Great Work, a profound commentary, or a revolution in webcomic storytelling. It was a messy, crowsourced text adventure that borrowed the visual language of video games. And it told its story through a glorious bricolage of forgettable old movie references, bewildering nods to current affairs, extra deep-fried JPEGs, and some of the most beautiful art I’ve ever seen in a comic.

In 2012, my grandfather, whom I had seen every day of the previous five years, passed away. In 2013, my father received what we all believed to be a terminal diagnosis. In two short years, I got to experience my world ending, and the struggle of learning how to carry on anyway.

I started writing Revolving Door in 2013, in between those two events. I continued writing it in tandem with my father’s evolving health condition. So it is a story that came fully from grief, from the universe-rending horror of being forced to confront not just death, but also the end of the world as I knew it.

That’s the part I’ve never seen anyone say about grief. It made me feel like I wasn’t living in the same world anymore, as if a new one had taken its place overnight. I had to come to terms with watching a person who had once held absolute authority over me become fully reliant on nurses and drips, unable even to go to the bathroom by himself. I had to come to terms with the idea that someone I loved could be conscious and lucid one day, and the next, gone.

More than ever, I had to grapple with the idea that once you die (at least if you don’t believe in an afterlife—which I don’t), you will no longer perceive the universe. And that is the same as the universe ending.

It was the single, ultimate fear: fear of the finiteness of life, and of the universe. The inevitable end of everything, which in retrospect would render all meaningless.

But I began to find comfort in the oddest idea. The idea that there is a way to live an infinity of years. To keep stretching out your time, to turn minutes into days, days into centuries.

You know that feeling of walking into a movie theatre, watching a groundbreaking film, and coming out wondering what year it is? Feeling like you experienced a decade of life in two short hours?

That was the only place of solace I ever found. There is no extending your life to two lifetimes, but there is living many lives in the timespan of one. Kind of.

And that’s the sentiment that I committed to Revolving Door. It was always meant to be a way to live—again and again, as different people—a way to live twelve years in a day. Each life a different universe, with its own internal logics, worldviews, moral quandaries.

It was also a reason to learn about lives and times that aren’t my own and to reaffirm that the people of the past have not truly vanished. A reminder that we can still access the lives of those who lived a millennium ago, and so someone a millennium from now might be able to know us, too, if only in abstract.

And, maybe most egocentrically, it was a way to document myself, my curiosities and knowledge and ignorance about the world. I don’t mean this in a biographical sense. My hope was simply that someone in the future would be able to pick RD up and discover who I was by reading it, by briefly inhabiting the mind that invented this story.

I have never intended for it to be an objective, all-encompassing document of the universe, some sort of Great Work…it’s hopelessly subjective, and biased, and me. It’s limited by what I know, perceive, and give a shit about. It’s not a document of the universe. It’s a document of me.

When I read Homestuck in 2014, I almost immediately wrote a letter to “future me.” You know those websites that let you draft a letter to a chosen email address, which is held in storage and then delivered to you a number of years later? Yeah, I wrote myself a letter that, in true smarmy Homestuck fashion, addressed my future self as if talking to a different person whose mind and soul I knew intimately.

I have always enjoyed the concept of communicating with my future self. I, in the present, remember how my past self felt about the world, and about their future, including what they would have liked to hear from their future self.

Back when I was 20, I worried about not finishing Revolving Door within 10 years. My past self put a lot of stock in the vigour of their youth—their boundless energy to write and keep writing, to spin a beautiful narrative for an audience, and the free time they had to do so. I was scared that I would lose that as I got older.

But those ten years have passed. I am now about to turn 31. And Revolving Door? Well, Revolving Door is still being written. And as of last week, the project is now fully outlined.

That’s a significant milestone: there now exists a 73,000 word document outlining the entire story of Revolving Door from start to end, and all the ingredients that will fill in the gaps. I now have, in my possession, a document that someone else could realistically pick up and use to complete the novel, should I die tomorrow.

I don’t think that the self of 2014, or the self of 2019, was in the right place to get the novel this far. They were too scared of the shame of being caught with their metaphorical pants down on the research front, too scared to be told that their chapter had fundamentally misrepresented that era or had been too simplistic in its portrayal of that war.

That’s what happens when you write a story about 12 different universes with fully realised stories, I guess. It’s like writing 12 novels concurrently. You end up having to build/research 12 universes. But gone are the days when I would spent a year or two on a single chapter. Repeatedly.

In the first 11 years of the story’s existence, I wrote 28 chapters. Three chapters a year. In 2024, I wrote 14 chapters.

What changed in 2024? Offshore, I think. Offshore was my 2022 NaNoWriMo novel about two offshore racing teammates and their very last race together.

I needed Offshore for a few reasons—for helping me process the increasingly tangled grief of having a family member die, another family member almost-die, moving to a different country, then being dumped by the ex I moved for.

I needed it because it showed me what the problem was. Thanks to Offshore, whose first draft took all of three weeks, I know I can write at a very high quality very quickly…if not for my fatal flaw of perfectionism. Perfectionism kept me pacing in circles over every single chapter.

So, now, I’ve hit my stride with RD, and I’ve written a third of its existing chapters in the past year. I don’t care if they’re less polished than the first 28, or less unrelentingly researched. Because the story won’t ever be complete, if they were.

And Revolving Door has to exist. In full. I made that vow to myself in 2013, and now I will make it happen.

Once I read Homestuck, I could never escape that it would bleed into the way I wrote RD. Because the two coincided so closely on the timeline of my life. Because the two are about the body as a metonym for the universe, the universe as a metonym for the body. As when Spades Slick shoots sn0wman through the heart and scratches Universe B.

When you die, and cease to perceive the universe, that’s no different from universe ending, no?

I think that was the fundamental parallel between the two works, which my friend had captured in a simple comparison between one of RD’s characters and one of Homestuck’s, all those years ago. It’s the reason I ever read Homestuck at all. And now, Homestuck’s self irreverence, and its playfulness with the conventions of genre and medium, have made themselves felt in everything I’ve made since. Including RD. Especially RD.

Homestuck is a story where the universe can disappear, and when it does, we aren’t just told that it happened. The video frame collapses and vanishes into the blank expanse of the webpage. You get to watch the mediating space—the webpage—wipe the world out.

You also get to see the links explode into branches when the timeline is splintered, or recurse on themselves when the timeline loops. It reveals, in a highly tactile way, the malleable, fractured, faceted nature of reality and the experience of it. It simulates the feeling of perceiving it all at once, and still not being able to make sense of it.

Because Homestuck’s thesis on reality is the only one I’ve seen that has made me feel at home with my mortality.

Other than the one in Revolving Door, I guess. But you’ll have to wait to find out why that is, because I’m still writing it.

Originally posted on Tumblr.